You know that feeling when you’ve been hard at work, all day, and you’re still not quite done? That was me a few nights ago. I set a milestone for myself (it was doing laundry, but that’s not important) and my reward was fishing through my cellar for one of the wines I had hidden away years ago. When I say cellar, what I really mean is cardboard box in my closet, so don’t get any ideas about my lavish lifestyle.

That experience gave me an idea for this article, to talk about bottle aging. I chose a 2017 Cabernet Sauvignon from Stags’ Leap1 in Napa Valley. I remembered tasting this wine about 5 years back and I was curious to see how it had developed, if at all, in bottle since then. First though, what is bottle aging anyway?

Defining Bottle Age

One thing you hear about wine, almost from the first statement, is that it improves with age. That is one of the most unfortunate and misleading statements that really anyone could make when introducing a newcomer to wine. It’s just not true for a vast majority of wines, regardless of their quality level. It does tell a great story for the media to get behind though.

So with that behind us, let’s define what this bottle aging thing is. The definition which I prescribe to is that a wine is “age-worthy” if it has some potential to *improve* by staying in bottle. More or less there is agreement on this definition across the wine industry, at least so far as the wine industry agrees on anything (hint, there is very little agreement). Note the big emphasis there on improvement. A wine that won’t necessarily improve but may stay the same, well what are you waiting for?

The Effects of Bottle Aging

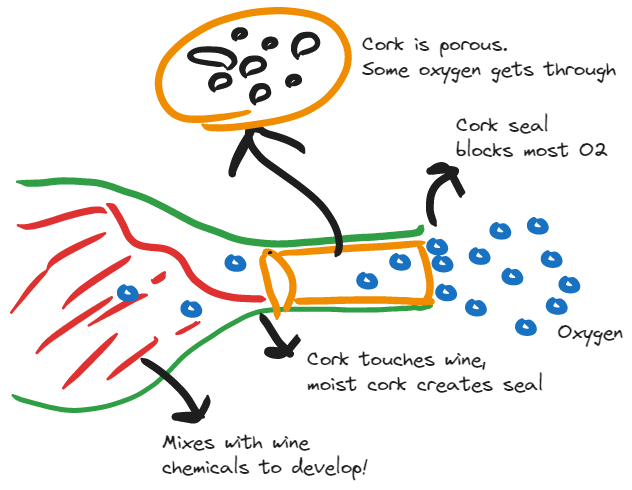

Now that we’ve established that to bottle age means to improve with time in the bottle let’s go deeper, but not too deep. What actually causes that improvement to take place is a more complex topic than I either claim to understand or have the space to write about after all. Generally speaking, slow oxygen contact through the enclosure interacts with various chemical compounds present in the wine and changes them, hopefully for the better. This also means for the bottle aging process to occur, the bottle’s enclosure must be partially permeable such as with natural cork, rather than an airtight seal as with some screw top bottles. Check out this handy diagram for a visual:

Once the oxygen is in the bottle, it changes the wine in a number of ways. Fresh fruit flavors, like just-picker berries or crisp apples as an example, may transition to be more similar to berry jam or dried apples. This trend of “fresh to dried” is very common with flavor development and temperature also plays a role. Some of these fruit flavors may transition entirely, such as from a red cherry flavor into something meaty and savory like is seen in the Sangiovese grape commonly used for Chianti. These interreacts are complex and the end result is not this predictable necessarily, but the trends are usually there.

Flavor isn’t the only part of a wine that is changed by this very slow oxidation however. The color of the wine will shift from a lemony-yellow to brown in bottle aged white wines (that’s right, white wines can also age in bottle). For red, the bright reddish color may develop into a rust or garnet and eventually to dark brown. Typically the reds also get a little more transparent than in their youth as well. Tannins, compounds that come from grape skins or seeds, can also develop from often astringent and sticky-feeling in the mouth at youth to softer flavor and texture sensations with age in bottle. All of these changes work together, hopefully, to create those deeply complex and interesting wines that you hear wine professionals rave about and in some ways is what makes wine such an interesting beverage to begin with.

Wine Time

As I mentioned earlier, I dug the 2018 Stags’ Leap, “The Leap”, Cabernet Sauvignon from my cellar the other night and enjoyed a glass after finishing the day’s chores. As I do with almost any wine when time and social circumstances allow, I also wrote up a quick tasting note on it.

As is typical with Cabernet Sauvignon, the wine had a deep ruby color with only slight opacity at the edge of the rim, though I could faintly see some slight browning as would be typical in an older wine. Pouring into the glass, the blackberry jam aroma was particularly obvious at standing distance. I don’t pay too much attention to the aromas while standing to be honest, but it’s a good feeling. Anecdotally it seems when pouring from a Coravin as I typically do, it often release much stronger initial aromas. Moving closer, the aromas were still quite a intense, with more developed flavors like dark chocolate, dried violets, and black liquorice. These are all aromas typical of bottle aging, where those fresher fruit notes have given way into something more “aged”. I was able to find a past tasting note for this wine from 2019, where interestingly enough I called out the fresher aromas of violet, ripe blackberry, and black plum so this is an excellent comparative example of what time in bottle can do to make wines more interesting with age.

Though the focus of my post here is bottle age, there are some other interesting points for The Leap. The wine had some slight smoked cedar and vanilla notes, which I’m going to attribute to time in new oak barrel rather than bottle. Especially with Napa Cabernet, the oak influence can be a bit a overpowering historically so I really appreciated the light touch here. In terms of structure, I found the wine to be exceptionally well balanced, just enough acidity to counteract grippy tannins and keep the wine interesting.

The Leap is an outstanding wine all around and it does carry a bit higher price tag to match. Given the cost of production in California, the notoriety of Napa Valley, and the dwindling supply of the 2017 vintage that’s probably not surprising.

Is it worth the ~$100/bottle cost though?

I’ll leave that for you to decide.

Funny story. There are actually two facilities with very similar names: Stags’ Leap Winery and Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars. To make it more confusing, they are also next to each other and mostly no one says full names. Essentially the differentiation is in that carefully-placed apostrophe.